Family Limited Partnerships: A lifeline in the IHT storm

In this article, we consider the impact of changes to UK inheritance tax (IHT) on the use of trusts by UK resident Americans and explore the use of family limited partnerships (FLPs) as an alternative vehicle for wealth planning.

Impact of changes to IHT since April 2025

Changes to IHT took effect on 6 April 2025 will be a significant concern to many UK resident Americans. After ten consecutive (or ten out of the prior 20) tax years of UK residence, those who come to the UK from the US will become exposed to IHT on their worldwide assets. IHT is charged at a flat rate of 40% on death to the extent that the value of the deceased’s estate exceeds his or her available ‘nil rate band’ (NRB) amount of up to £325,000.

While those who are US citizens or domiciliaries will already have a worldwide exposure to US estate tax at up to 40% on death (and, in principle, the treaty between the US and the UK should prevent double taxation) the UK exposure represents a real additional tax cost. This is down to the size of the US federal estate tax exemption that is currently available to US citizens and domiciliaries, of up to $13.99m per individual in 2025 (and due to increase to $15m in 2026). In effect, the worldwide IHT exposure gives rise to an additional tax liability equal to 40% of the difference between the available NRB amount and the available US estate tax exemption of the deceased (or the total value of their estate if it is less than the available US exemption) on death. Based on a USD:GBP exchange rate of 1: 0.75, this represents a real additional tax cost of up to $5.42m per individual estate.

Historically, many UK resident Americans who were expecting to remain in the UK long enough to acquire a worldwide exposure to IHT (which would occur after 15 years of UK residence under previous rules) would have taken steps in advance of the change to mitigate the adverse implications. Most commonly, they would do this by transferring some or all of their non-UK assets into trust. By doing so, under IHT rules at the time, they could shelter those assets from IHT indefinitely, even if they were able to benefit from the trust. Under new rules, this planning will no longer be effective where the trust is funded on or after 30 October 2024. Instead, the trust assets will form part of the settlor’s estate for IHT purposes on death unless the settlor is excluded from benefit irrevocably. The trust assets will also be exposed to IHT charges of up to 6% every ten years and on ‘exits’ (such as capital distributions) from the trust between ten-year anniversaries for so long as the settlor retains a worldwide exposure to IHT.

There may still be opportunities for US citizens and domiciliaries (who are not also UK citizens) to leverage the US-UK estate and gift tax treaty to protect their non-UK assets from IHT through transfers into trust, but the scope for this is now significantly more limited than it has been previously. Therefore, UK resident Americans who are concerned about IHT will want to explore alternative planning strategies.

Considering alternative IHT planning strategies

It will, of course, remain important to think about how assets can pass efficiently on death. As a minimum, married couples should look to structure their wills in a way that allows access to the spouse exemption from IHT on the first death, postponing any IHT liability until they have both died. If both spouses are in good health, they may find they are able to obtain life insurance on their joint lives relatively cheaply to cover the IHT bill that arises on the second death. This can be a good option alone where substantial lifetime gifts are not viable, or it can be used in combination with a gifting strategy. Life policies taken out for this purpose should be written into trust to prevent the death benefit itself from being subject to IHT.

Potentially Exempt Transfer (PET) regime remains intact

Contrary to speculation in the run-up to the 2024 Autumn Budget, the UK’s PET regime remains intact following the April 2025 changes. This regime allows outright gifts in any amount to be made free of IHT if the donor survives the gift by seven years (with a reduced rate of IHT applying if the donor survives by more than three but less than seven years). Making PETs can be a powerful IHT planning tool in the right circumstances. In theory, this could allow a person to give away everything they have free of IHT during lifetime! However, there are important non-tax considerations to factor in.

First, the donor must be able to afford to give the relevant assets away. Anti-avoidance rules (known as the ‘gift with reservation of benefit’ rules) prevent the donor from ‘having his cake and eating it’, so it will be critical for the donor to cease his own enjoyment of the relevant assets at the time of the gift. Secondly, the donor must be prepared to make the gift with ‘no strings attached’. The gift must be absolute, and the donee must be free to do as he chooses with the relevant assets, which will belong to him. The donor is required to give up all formal control and ownership rights upon making the gift, which could reduce the appeal of this planning where there are concerns regarding asset protection and/or how the relevant assets will be used by the donee.

Family Investment Company (FIC) structures

This dilemma has led many to explore the use of structures through which the PET regime can be leveraged while at the same time incorporating some of the control and asset protection benefits associated with trusts. A popular structure has been the FIC. As the name suggests, a FIC is a private company that is created for the purposes of holding investments for a family. The allocation of shares and the associated rights of shareholders can be tailored to the family’s needs and can allow the division of voting control and economic interests between different generations. Gifts of shares (or funds for children to subscribe for shares) in the FIC will be PETs for IHT purposes, but control mechanisms can be built in via the company’s articles and by agreement between shareholders, which can make this option more attractive than making outright gifts of cash.

However, the use of FICs presents various challenges for American donors and donees. Active steps would need to be taken to prevent the FIC becoming entangled in penal US anti-avoidance rules that apply to ‘passive foreign investment companies’ (PFICs). Where the PFIC regime applies, the US imposes onerous income tax and interest charges on certain distributions and profits made by the FIC. Even if this can be managed (for instance, by making a ‘check the box’ election to make the entity transparent for US tax purposes), the structure presents a risk of double taxation if profits are extracted from it by UK resident family members. This generally limits the effectiveness of the planning to scenarios where the family can afford not to benefit from the FIC while they are UK resident.

The appeal of FLPs

FLPs can offer similar non-tax advantages to FICs, but without the same penal anti-avoidance rules and double tax risks. This is because an FLP is, by default, transparent for tax purposes in both the US and the UK. Therefore, the partners are subject to tax on their respective shares of the partnership’s income and gains directly as they arise.

How do they work?

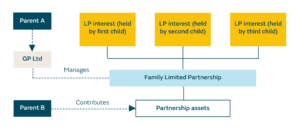

In a typical FLP structure, the parent/grandparent will fund the FLP in exchange for limited partner (LP) and general partner (GP) interests. The GP interest (to which minimal economic value will be attributed) will hold the management rights, including strategic decision-making powers and control over the FLP’s distribution policy. The GP interest will often be held through a limited company to provide de facto limited liability. LP interests (including a pro-rated share of profits) will be given by the parent/grandparent to his children/grandchildren. A partnership agreement will be put in place that is bespoke to the family’s requirements. This is likely to incorporate control mechanisms and seek to provide a degree of asset protection for the partners – e.g. by incorporating limits on transfers of interests, admission to the partnership, redemption of capital, exercise of voting rights, etc. The GP interest will sometimes be retained by the donor, but more often will be transferred to a spouse or third party to mitigate the risk of the donor reserving powers that prevent the gifts from being ‘completed’ for US transfer tax purposes.

Tax considerations

No liability to tax should arise in the US or the UK on the initial funding of the FLP by the donor because there will not be any change to the beneficial ownership of the underlying assets. From a transfer tax perspective, the gifts of the LP interests will be PETs for IHT purposes, so will pass free of IHT if the donor survives the gifts by seven years. If the donor is a US citizen or domiciliary, the gifts will also be subject to US gift tax, but no liability will arise if the value of the gifts falls within the donor’s available exclusion amounts. When assessing the value of the gifts for tax purposes, there may be discounts available for minority interests and lack of marketability. Future growth on the assets will occur outside the donor’s estate for IHT and US estate tax purposes.

Although the gifts of the LP interests will not constitute ‘gain recognition events’ for US income tax purposes, they will represent disposals of the underlying assets for UK capital gains tax (CGT) purposes. This could mean it is preferable to fund the FLP with cash or, where the FLP is funded with assets in specie, to structure the transfers as gifts of cash, followed by sales of the LP interests. The sales will trigger tax on uncrystallised gains in both the US and the UK, but relief should be available under the US-UK income tax treaty to prevent double taxation.

Non-tax considerations

FLPs offer a mechanism to pass wealth to younger generations while retaining a degree of control and protection over the underlying economic interests. In many respects, this separation of control and economic ownership is reminiscent of a trust structure, which is attractive. However, this must be balanced against other non-tax considerations related to the use of FLPs. In particular:

-

- Because FLPs are transparent for tax purposes, they will give rise to tax liabilities for the limited partners, even if no distributions are made. This exposure to tax on the profits of the FLP means the limited partners will require full transparency regarding the finances of the partnership, to enable them to comply with their personal tax reporting obligations. There will be little mystery as to the value of their interests!

-

- There will be substantial professional costs associated with the setup and maintenance of the structure, including annual compliance costs for the FLP and its partners.

Historically, there have also been concerns that the general partners of FLPs might require regulatory oversight by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). However, the FCA has indicated that this is not necessarily the case for family FLPs.

In a nutshell:

Recent changes to UK inheritance tax will be a concern to many UK resident Americans, who may want to explore new IHT planning strategies. For UK tax reasons, the use of trusts as vehicles for lifetime gifting may be unappealing for those that are not able to benefit from relief under the US-UK estate and gift tax treaty. While UK tax rules favour outright gifts as an IHT planning tool, there are non-tax factors that can prohibit or limit the appeal of lifetime giving. FLP structures can offer a tax-efficient and flexible solution, which balances the desire to reduce the size of the donor’s estate with the need for a controlled transfer of wealth to younger generations.

Disclaimer

The members of our US/UK team are admitted to practise in England and Wales and cannot advise on foreign law. Comments made in this article relating to US tax and legal matters reflect the authors’ understanding of the US position, based on experience of advising on US-connected matters. The circumstances of each case vary, and this article should not be relied upon in place of specific legal advice.

Your guide to US-UK cross-border planning

If you have connections to the US and the UK you’ll need to navigate between two very different regimes. Understand the issues, avoid the traps and discover ways to plan ahead.

Visit our Navigating the Atlantic hub