Tricky transatlantic nuptial agreements – Considerations for HNW individuals and their advisors

The US and the UK are separated by the vast and tumultuous waters of the Atlantic Ocean. Those with connections to both countries will often find themselves rowing against the tide between two very different and complex regimes. With the right specialist advice, they can navigate the cross-border challenges safely and make the best use of planning opportunities.

Understand the issues, avoid the traps, and discover ways to plan ahead in our Navigating the Atlantic series for US-connected clients.

In this instalment, we consider the impact of changes to UK inheritance tax (IHT) on the use of trusts by UK resident Americans and explore the use of family limited partnerships (FLPs) as an alternative vehicle for wealth planning.

Changes to IHT that are due to take effect on 6 April 2025 will be a significant concern to many UK resident Americans. After ten consecutive (or ten out of the prior 20) tax years of UK residence, those who come to the UK from the US will become exposed to IHT on their worldwide assets. IHT is charged at a flat rate of 40% on death to the extent that the value of the deceased’s estate exceeds his or her available ‘nil rate band’ (NRB) amount of up to £325,000.

While those who are US citizens or domiciliaries will already have a worldwide exposure to US estate tax at up to 40% on death (and, in principle, the treaty between the US and the UK should prevent double taxation) the UK exposure represents a real additional tax cost. This is down to the size of the US federal estate tax exemption that is currently available to US citizens and domiciliaries, of up to $13.99m per individual in 2025. In effect, the worldwide IHT exposure gives rise to an additional tax liability equal to 40% of the difference between the available NRB amount and the available US estate tax exemption of the deceased (or the total value of their estate if it is less than the available US exemption) on death. Based on a USD:GBP exchange rate of 1: 0.8, this represents a real additional tax cost of up to $5.43m per individual estate.

Historically, many UK resident Americans who were expecting to remain in the UK long enough to acquire a worldwide exposure to IHT (which would occur after 15 years of UK residence under current rules) would have taken steps in advance of the change to mitigate the adverse implications. Most commonly, they would do this by transferring some or all of their non-UK assets into trust. By doing so, under IHT rules at the time, they could shelter those assets from IHT indefinitely, even if they were able to benefit from the trust. Under new rules, this planning will no longer be effective where the trust is funded on or after 30 October 2024. Instead, the trust assets will form part of the settlor’s estate for IHT purposes on death unless the settlor is excluded from benefit irrevocably. The trust assets will also be exposed to IHT charges of up to 6% every ten years and on ‘exits’ (such as capital distributions) from the trust between ten-year anniversaries for so long as the settlor retains a worldwide exposure to IHT.

There may still be opportunities for US citizens and domiciliaries (who are not also UK citizens) to leverage the US-UK estate and gift tax treaty to protect their non-UK assets from IHT through transfers into trust, but the scope for this will be significantly more limited than it has been previously. Therefore, UK resident Americans who are concerned about IHT will want to explore alternative planning strategies.

It will, of course, remain important to think about how assets can pass efficiently on death. As a minimum, married couples should look to structure their wills in a way that allows access to the spouse exemption from IHT on the first death, postponing any IHT liability until they have both died. If both spouses are in good health, they may find they are able to obtain life insurance on their joint lives relatively cheaply to cover the IHT bill that arises on the second death. This can be a good option alone where substantial lifetime gifts are not viable, or it can be used in combination with a gifting strategy. Life policies taken out for this purpose should be written into trust to prevent the death benefit itself from being subject to IHT.

Potentially Exempt Transfer (PET) regime remains intact

Contrary to speculation in the run-up to the Autumn Budget, the UK’s PET regime is to be left intact following the April 2025 changes. This regime allows outright gifts in any amount to be made free of IHT if the donor survives the gift by seven years (with a reduced rate of IHT applying if the donor survives by more than three but less than seven years). Making PETs can be a powerful IHT planning tool in the right circumstances. In theory, this could allow a person to give away everything they have free of IHT during lifetime! However, there are important non-tax considerations to factor in.

First, the donor must be able to afford to give the relevant assets away. Anti-avoidance rules (known as the ‘gift with reservation of benefit’ rules) prevent the donor from ‘having his cake and eating it’, so it will be critical for the donor to cease his own enjoyment of the relevant assets at the time of the gift. Secondly, the donor must be prepared to make the gift with ‘no strings attached’. The gift must be absolute, and the donee must be free to do as he chooses with the relevant assets, which will belong to him. The donor is required to give up all formal control and ownership rights upon making the gift, which could reduce the appeal of this planning where there are concerns regarding asset protection and/or how the relevant assets will be used by the donee.

Family Investment Company (FIC) structures

This dilemma has led many to explore the use of structures through which the PET regime can be leveraged while at the same time incorporating some of the control and asset protection benefits associated with trusts. A popular structure has been the FIC. As the name suggests, a FIC is a private company that is created for the purposes of holding investments for a family. The allocation of shares and the associated rights of shareholders can be tailored to the family’s needs and can allow the division of voting control and economic interests between different generations. Gifts of shares (or funds for children to subscribe for shares) in the FIC will be PETs for IHT purposes, but control mechanisms can be built in via the company’s articles and by agreement between shareholders, which can make this option more attractive than making outright gifts of cash.

However, the use of FICs presents various challenges for American donors and donees. Active steps would need to be taken to prevent the FIC becoming entangled in penal US anti-avoidance rules that apply to ‘passive foreign investment companies’ (PFICs). Where the PFIC regime applies, the US imposes onerous income tax and interest charges on certain distributions and profits made by the FIC. Even if this can be managed (for instance, by making a ‘check the box’ election to make the entity transparent for US tax purposes), the structure presents a risk of double taxation if profits are extracted from it by UK resident family members. This generally limits the effectiveness of the planning to scenarios where the family can afford not to benefit from the FIC while they are UK resident.

FLPs can offer similar non-tax advantages to FICs, but without the same penal anti-avoidance rules and double tax risks. This is because an FLP is, by default, transparent for tax purposes in both the US and the UK. Therefore, the partners are subject to tax on their respective shares of the partnership’s income and gains directly as they arise.

How do they work?

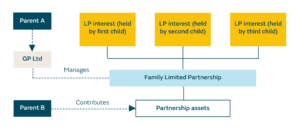

In a typical FLP structure, the parent/grandparent will fund the FLP in exchange for limited partner (LP) and general partner (GP) interests. The GP interest (to which minimal economic value will be attributed) will hold the management rights, including strategic decision-making powers and control over the FLP’s distribution policy. The GP interest will often be held through a limited company to provide de facto limited liability. LP interests (including a pro-rated share of profits) will be given by the parent/grandparent to his children/grandchildren. A partnership agreement will be put in place that is bespoke to the family’s requirements. This is likely to incorporate control mechanisms and seek to provide a degree of asset protection for the partners – e.g. by incorporating limits on transfers of interests, admission to the partnership, redemption of capital, exercise of voting rights, etc. The GP interest will sometimes be retained by the donor, but more often will be transferred to a spouse or third party to mitigate the risk of the donor reserving powers that prevent the gifts from being ‘completed’ for US transfer tax purposes.

Tax considerations

No liability to tax should arise in the US or the UK on the initial funding of the FLP by the donor because there will not be any change to the beneficial ownership of the underlying assets. From a transfer tax perspective, the gifts of the LP interests will be PETs for IHT purposes, so will pass free of IHT if the donor survives the gifts by seven years. If the donor is a US citizen or domiciliary, the gifts will also be subject to US gift tax, but no liability will arise if the value of the gifts falls within the donor’s available exclusion amounts. When assessing the value of the gifts for tax purposes, there may be discounts available for minority interests and lack of marketability. Future growth on the assets will occur outside the donor’s estate for IHT and US estate tax purposes.

Although the gifts of the LP interests will not constitute ‘gain recognition events’ for US income tax purposes, they will represent disposals of the underlying assets for UK capital gains tax (CGT) purposes. This could mean it is preferable to fund the FLP with cash or, where the FLP is funded with assets in specie, to structure the transfers as gifts of cash, followed by sales of the LP interests. The sales will trigger tax on uncrystallised gains in both the US and the UK, but relief should be available under the US-UK income tax treaty to prevent double taxation.

Non-tax considerations

FLPs offer a mechanism to pass wealth to younger generations while retaining a degree of control and protection over the underlying economic interests. In many respects, this separation of control and economic ownership is reminiscent of a trust structure, which is attractive. However, this must be balanced against other non-tax considerations related to the use of FLPs. In particular:

Historically, there have also been concerns that FLPs may be treated as collective investments schemes, requiring regulatory oversight by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA). However, the FCA has confirmed that this is not relevant to single family FLPs.

Upcoming changes to UK inheritance tax will be a concern to many UK resident Americans, who may want to explore new IHT planning strategies. For UK tax reasons, the use of trusts as vehicles for lifetime gifting will become unappealing and ineffective in many cases. While UK tax rules favour outright gifts as an IHT planning tool, there are non-tax factors that can prohibit or limit the appeal of lifetime giving. FLP structures can offer a tax-efficient and flexible solution, which balances the desire to reduce the size of the donor’s estate with the need for a controlled transfer of wealth to younger generations.

The members of our US/UK team are admitted to practise in England and Wales and cannot advise on foreign law. Comments made in this article relating to US tax and legal matters reflect the authors’ understanding of the US position, based on experience of advising on US-connected matters. The circumstances of each case vary, and this article should not be relied upon in place of specific legal advice.

Emma Gillies and Rebecca Anstey on why the proposed abolition of the UK’s non-dom regime will have little impact on many UK resident Americans.

The UK government has proposed changes to the taxation of non-UK domiciled, UK residents from 6 April 2025.

Individuals will be looking to their advisors for help navigating these changes and those advising US citizens will need to understand how the new rules affect their clients.

The interaction between US and UK tax laws means that US citizens residing in or moving to the UK may not be as concerned as others by the changes, but there are still challenges and potential planning opportunities to be aware of.

It will be old news to many that the UK government plans to introduce changes to the tax treatment of non-UK domiciled, UK-resident individuals (so-called ‘non-doms’) with effect from 6 April 2025. Although many non-doms will have concerns about the impact of the new regime, US non-doms should be sheltered from the fallout more than most.

Abolition of the remittance basis

Non-doms can currently claim the remittance basis of taxation. Those who do are subject to tax on their UK-source income and capital gains as they arise, but only on non-UK income and gains if and to the extent that they are ‘remitted’ to (broadly, brought to or used in) the UK.

It is proposed that the remittance basis will be abolished and replaced by a new ‘foreign income and gains’ (FIG) regime. Under the FIG regime, those who have not been UK resident in any of the previous ten years will be exempt from tax on their non-UK income and gains during their first four years of residence (regardless of any remittances). Thereafter, they will become subject to tax on their worldwide income and gains as they arise.

In many cases, the loss of access to the remittance basis will not be a major concern to US non-doms.Unlike most non-doms, US citizens are already exposed to tax (in the US) on their worldwide income and gains as they arise. Fortunately, there is a treaty in place between the UK and the US that is designed to provide relief from double taxation where a liability arises in both countries at the same time. A UK-resident US citizen (with exposure to tax in both countries under domestic rules) may be able to show that they should be treated as tax resident in the US for the purposes of the treaty, at least for the early years of residence when their ties to the US remain strong. In these cases, their exposure to UK tax will be limited to certain types of UK income, with no need to claim the remittance basis on their foreign income and gains.

Where the taxpayer is resident in the UK for the purposes of the treaty, they will generally be exposed to tax at the higher of the two countries’ effective rates on a given item of income or gain. In that scenario, the utility of the remittance basis is generally limited to avoiding the risk of double taxation. This can be helpful where an item of income or gain is treated differently in the UK and the US, and treaty relief is not available. It can also assist in avoiding a higher rate of tax in the UK than is payable in the US; for example, on investment returns from US mutual funds that do not have ‘reporting’ status in the UK, which are taxed at capital gains rates (20 per cent) in the US but income tax rates (45 per cent) in the UK.

For these reasons, it is uncommon for US non-doms to claim the remittance basis beyond the point at which it comes at the cost of an annual charge (i.e., from the beginning of the eighth consecutive tax year of residence). Before that, it can be convenient to claim the remittance basis from a reporting perspective. However, using the remittance basis to defer UK tax is generally not wise for US citizens, because a mismatch in the timing of the UK and US liabilities can often cause a loss of treaty relief, resulting (ironically) in double taxation. It should only really be used where the taxpayer is confident that their foreign income and gains will never be remitted to the UK.

Removal of ‘protected settlement’ status for ‘settlor-interested’ trusts

Under current rules, where a non-dom settles assets into a non-UK-resident trust, the trust’s non-UK source income and capital gains are generally sheltered from tax unless and until a UK-resident individual receives a benefit from the trust, at which point a liability may be triggered. It looks as though the protected’ status of these trusts will no longer be available under the new regime. Instead, where the UK-resident settlor retains an interest in the trust (within the relevant statutory definitions) it is proposed that the trust’s worldwide income and gains will be treated as arising to the settlor, and will be taxed accordingly.

Again, this change will be of less concern to many US settlors, who will have deliberately put their trusts outside the ‘protected settlement’ regime, having been advised to do so on the basis of double taxation risks. These arise because most lifetime trusts settled by US citizens will be grantor trusts for US income tax purposes, meaning the income and gains of the trust are taxed on the settlor as they arise. The resulting mismatch in the timing of the tax liability (immediate in the US versus deferred in the UK) and, potentially, the identity of the taxpayer (settlor in the US versus beneficiary in the UK) will often cause a loss of treaty relief. By contrast, maximum relief should be available if the income and gains are taxed on the settlor in both the UK and the US as they arise.

Changes to UK IHT

Under current rules, non-doms who are not deemed domiciled in the UK (because they have not been resident in 15 or more of the past 20 tax years) are only subject to UK inheritance tax (IHT) on UK assets. Under the new regime, domicile will no longer be relevant when assessing IHT. Instead, a person will become exposed to IHT on worldwide assets after ten years’ tax residence in the UK.

The deemed domicile ‘tail’

Currently, where a non-dom becomes deemed domiciled, they

will continue to be deemed domiciled for IHT purposes for a

further four tax years after ceasing UK residence. Under the new

regime, it is proposed that this IHT ‘tail’ will be extended to ten

years.

Thanks to the US-UK Estate and Gift Tax Convention (the Treaty), US citizens who leave the UK to return to the US will lose this ‘tail’ much sooner than other non-doms, provided they can show they are US resident for the purposes of the Treaty (and they are not UK citizens). In that scenario, the US will have exclusive taxing rights over the estate, save for UK immovable property or business property of a permanent establishment (BPPE).

Excluded property trusts

Until now, assets transferred into trust by non-doms (including US citizens) who are not yet deemed domiciled are excluded from IHT indefinitely (hence the term, ‘excluded property trusts’).

The government has announced that trust assets will no longer be excluded from IHT. However, some US citizens may be able to rely on the Treaty to achieve the same result. The Treaty provides that no IHT is due on trust assets (other than UK real estate and BPPE) settled by someone who was domiciled in the US and not a UK citizen. If the treaty continues to apply in the same way under the new regime (with UK domicile interpreted to mean ten years’ UK tax residence), assets settled into trust by US citizens who are not UK citizens and have not yet spent ten years in the UK may be protected from IHT beyond the ten-year threshold.

Tradition abolition, Emma Gillies and Rebecca Anstey, STEP Journal (Vol32, Iss5)

The US and the UK are separated by the vast and tumultuous waters of the Atlantic Ocean. Those with connections to both countries will often find themselves rowing against the tide between two very different and complex regimes. With the right specialist advice, they can navigate the cross-border challenges safely and make the best use of planning opportunities.

Understand the issues, avoid the traps, and discover ways to plan ahead in our Navigating the Atlantic series for US-connected clients.

In this instalment, we explore the impact of HMRC’s recently updated guidance on the UK tax treatment of US LLCs and why planning ahead is more important than ever to avoid double taxation.

On 12 December 2023 HMRC published updated guidance (issued in International Manual 180050, see also 161040) on the UK tax treatment of profits arising within a limited liability company (an “LLC”) incorporated in the US. The guidance indicates that taxpayers will face an uphill struggle if they now wish to claim double tax relief on the basis of the decision of the United Kingdom’s Supreme Court in Anson v HMRC [2015] UKSC 44 (“Anson”).

In Anson, the taxpayer (Mr Anson), who was UK resident, was a member of a Delaware incorporated LLC. The profits of the LLC were apportioned between and distributed each quarter to its members. The LLC was classified as a partnership for US tax purposes and was, therefore, transparent for US federal and state tax purposes: Mr Anson (and not the LLC) was liable to US tax on his share of the profits as they arose.

HMRC sought to charge Mr Anson to UK income tax on the profits he received from the LLC (i.e. on the distributions) and argued that the profits that had been taxed in the US were the profits of the LLC and not of Mr Anson. On that basis, they argued that Mr Anson was not entitled to the benefit of the US/UK double tax treaty because the US tax and the UK tax were not payable on the same profits.

The First-tier tribunal (“the FTT”) found in Mr Anson’s favour, finding as fact that under Delaware law the profits of the LLC belonged to the members and not to the LLC. The case ultimately reached the Supreme Court, which also found in favour of Mr Anson by virtue of the FTT’s finding of fact: if Mr Anson’s share of the profits belonged to him under Delaware law, the distribution of his profits to him represented the mechanics by which he received the profits to which he was entitled and did not represent a separate profit source. As both US and UK tax arose on the same profits, Mr Anson was able to benefit from relief under the US/UK double tax treaty.

Shortly after the Supreme Court’s decision in Anson, HMRC published guidance in which they stated that “HMRC has after careful consideration concluded that the decision is specific to the facts found in the case…Individuals claiming double tax relief and relying on the Anson v HMRC decision will be considered on a case by case basis.”

Perhaps tellingly HMRC also said that “where US LLCs have been treated as companies within a group structure HMRC will continue to treat the US LLCs as companies, and where a US LLC has itself been treated as carrying on a trade or business, HMRC will continue to treat the US LLC as carrying on a trade or business”. HMRC’s guidance reassured the corporate community that group relief would continue to be available where US LLCs were part of the group structure.

Although not particularly helpful, this guidance suggested that HMRC conceded that where the facts of a case and those found in Anson were alike, the profits of an LLC should be treated as belonging to its members such that double taxation relief would be available.

However, it appears from the latest guidance that HMRC has decided to take a more robust approach. In INTM180050 HMRC now state: “Based on HMRC’s understanding of Delaware LLC law (as at 06 December 2023), and contrary to the conclusion reached by the FTT in HMRC v Anson…HMRC continue to believe that the profits of an LLC will generally belong to the LLC in the first instance and that members will generally not be treated as “receiving or entitled to the profits”of an LLC.”

HMRC go on to say that it understands that the LLC law of the other US states is largely the same as that of Delaware so that it would generally not regard the profits of other US LLCs as belonging as they arise to the members.

From HMRC’s perspective it follows that individual members will only be chargeable to UK tax on any dividends or other distributions that they receive from the LLC (a consequence of HMRC continuing to regard LLCs as being ‘opaque’ for UK tax purposes), and that such receipts will be taxed at the dividend rate of income tax (currently up to 39.35%). If the LLC is taxed as a partnership in the US, HMRC warns that in its view no relief is available under the treaty because it believes the same income is not being taxed in both jurisdictions.

Based on HMRC’s 2015 guidance taxpayers with similar facts to Anson were claiming treaty relief but in its new guidance HMRC say that where a taxpayer has claimed such relief, “HMRC will consider opening an enquiry or making a discovery assessment in accordance with its normal riskbased approach.”

For UK resident individuals who are members of US LLCs, the significance of the latest guidance is that HMRC is putting the taxpayer on notice that it disagrees with the FTT’s finding of fact in respect of Delaware law; as this finding underpinned the Supreme Court’s decision that Mr Anson could claim double tax relief, HMRC are now asserting that taxpayers with similar facts to Anson cannot rely on that decision to claim such relief.

Whilst the FTT’s finding in relation to Delaware law is treated as a finding of fact and therefore does not set a binding precedent for future cases, the Supreme Court considered that the FTT was entitled to make its findings about the interaction between Delaware legislation and the LLC’s operating agreement (it is generally understood that the LLC in Anson was not unusual). Further, as HMRC’s revised position is not based on new law but merely disagreement with the decision in Anson, it remains open for taxpayers to continue to file on the basis of Anson (with appropriate disclosure in the tax return).

The latest guidance indicates that HMRC are likely to push back on any attempt by a taxpayer simply to rely on Anson and may intend to re-litigate the point (albeit largely running the same arguments). HMRC may or may not win on any re-run of the Anson litigation. However, unless a taxpayer is determined to fight the point, if possible, we would suggest that it would be more time and cost effective for a taxpayer to structure their affairs so as to avoid the risk of double taxation. For example, to the extent possible, taxpayers could:

There is a certain policy logic for HMRC’s revised guidance which doubles down on its view that US LLCs should generally be treated as ‘opaque’ (often the desired treatment from a UK corporation tax perspective); HMRC’s position enables it to adopt a more uniform approach that, in practice, does not require it to review the relevant state legislation and an LLC’s operating agreement in every case.

However, it is an unsatisfactory outcome for individual taxpayers, particularly for those who want to receive their distributions in the UK and who justifiably wish to rely on the Supreme Court decision to benefit from treaty relief but do not want to incur the expense of challenging HMRC’s updated view. Taxpayers who want certainty of treatment may have to either accept an unpalatable double tax cost or see if they can structure or restructure their affairs accordingly.

The members of our US/UK team are admitted to practise in England and Wales and cannot advise on foreign law. Comments made in this article relating to US tax and legal matters reflect the authors’ understanding of the US position, based on experience of advising on US-connected matters. The circumstances of each case vary, and this article should not be relied upon in place of specific legal advice.

This article has also been published in ePrivateClient, which can be found here.

The US and the UK are separated by the vast and tumultuous waters of the Atlantic Ocean. Those with connections to both countries will often find themselves rowing against the tide between two very different and complex regimes.

With the right specialist advice, they can navigate the crossborder challenges safely and make the best use of planning opportunities. Understand the issues, avoid the traps, and discover ways to plan ahead in our Navigating the Atlantic series for US connected clients.

In this instalment, we bust some of the common myths when it comes to gifting and compare the tax implications of gifting in the US and the UK.

It is a common misconception that gifts to spouses and civil partners are completely exempt from transfer taxes in both jurisdictions. However, such gifts may be taxable where there is a mismatch in the tax status of the donor (the person making the gift) and the donee (the person receiving the gift).

UK

In the UK, there is generally an unlimited exemption from inheritance tax (“IHT”) on gifts between spouses and civil partners. However, where assets pass from a UK domiciled (or deemed domiciled) spouse to a non-UK domiciled spouse, the exemption is limited to just £325,000. Gifts in excess of this will be subject to tax in the same way as gifts made to any other individual.

There is an option for the non-UK domiciled recipient spouse to elect to be treated as domiciled for IHT purposes (in order to access the unlimited exemption) but this would also have the effect of bringing their non-UK assets within the scope of IHT, which may not be desirable. This will need to be considered carefully, on a case-bycase basis.

US

In the US, there is also an unlimited marital deduction from gift and estate tax on transfers to spouses in most cases. However, this will not be available where the donee spouse is not a US citizen. In that scenario, tax-free transfers in lifetime are limited to $175,000 annually (in 2023). In order to access the marital deduction from estate tax on death, assets have to be left to the non-US spouse in a special type of marital trust, known as a “QDOT”.

UK

In the UK, in order for a gift to charity to qualify for the charitable exemption from IHT, the recipient entity must not only be operating for ‘charitable purposes’ (as defined in UK legislation), but it must also be registered as a charity in a country of the UK, EU or EEA. Critically, this means that a gift to a US charity will not qualify for the exemption, no matter how worthy the charitable cause. Lifetime transfers to non-qualifying charities can trigger immediate IHT charges (as well as charges to UK capital gains tax on assets gifted in specie, as discussed below).

US

While the US imposes equivalent geographical limitations for income tax purposes (i.e. a charitable gift must be made to a US organisation to qualify for relief), this limit does not apply for US estate tax purposes where charitable bequests are made by US citizens and domiciliaries. Non-US citizens/domiciliaries, however, must leave US situs property to a US organisation to qualify for the US estate tax charitable deduction.

US

In the US, gratuitous transfers of appreciated assets will not constitute chargeable disposals for US income tax purposes – i.e. any in-built capital gain will not be crystallised on such transfers. Instead, the donor’s base cost in the assets will be “carried over” to the donee and will be used to compute the gains realised on the eventual disposal of the assets by them.

UK

One might assume that the same will be the case in the UK, but that assumption would be incorrect. In the UK, with certain limited exceptions, a gift of an asset will be a chargeable disposal for capital gains tax purposes. If chargeable gains are triggered in the UK but not in the US on the same event, this can give rise to a risk of double taxation because the mismatch in treatment can cause a loss of relief under the US-UK double tax treaty. Advice should be sought on aligning the treatment in both countries to maximise relief.

UK

In the UK, outright lifetime gifts to individuals will generally be subject to the ‘potentially exempt transfer’ (“PET”) regime. This means they will pass out of the donor’s estate free of IHT if the donor survives the gift by seven years or more. If the donor survives the gift by more than three years but less than seven, the gifted sum will be subject to IHT on the donor’s death, but at a reduced rate. The PET regime can be extremely advantageous for individuals who can afford to make substantial lifetime gifts, as there are no limits on the amount that can be given away to the next generation taxfree under this regime.

US

However, those who are subject to US gift and estate tax will be limited in their lifetime giving, as there is no equivalent to the PET regime in the US. Instead, US citizens and domiciliaries are broadly limited to making annual gifts to (any number of) individuals of up to $17,000 (in 2023) and otherwise eating into their lifetime exclusion amount of $12.92 million. Gifts in excess of these amounts are typically subject to immediate US gift tax at a rate of 40%, which is likely to be prohibitive in most cases.

US

It is common planning for US citizens and domiciliaries to make substantial lifetime transfers of assets into trust. By doing so, they can potentially remove assets (and any future growth on those assets) from their estates for US estate tax purposes. Provided the value of the assets transferred falls within their lifetime exclusion amount for gift and estate tax, this can be done without triggering tax.

UK

By contrast, in the UK, transfers of assets into trust are immediately subject to IHT (subject to available exemptions or reliefs). IHT is charged at a rate of 20% to the extent that the value of the assets transferred exceeds the donor’s available ‘nil rate band’ of up to £325,000. This IHT charge will be “topped up” to a maximum of 40% in the event that the donor dies within five years of the transfer. For UK domiciled (or deemed domiciled) individuals, this will be relevant to transfers of any assets, worldwide. For non-UK domiciled individuals, this will apply to transfers of UK assets only. Where it is relevant, this IHT charge will generally prohibit lifetime planning using trusts.

It is clear that gifting is an area that can cause significant difficulties for individuals with tax connections in the US and the UK. It is extremely important that advice is taken from advisors with an understanding of how the two legal systems interact; ideally before any action is taken.

The members of our US/UK team are admitted to practise in England and Wales and cannot advise on foreign law. Comments made in this article relating to US tax and legal matters reflect the authors’ understanding of the US position, based on experience of advising on USconnected matters. The circumstances of each case vary, and this article should not be relied upon in place of specific legal advice.

The US and the UK are separated by the vast and tumultuous waters of the Atlantic Ocean. Those with connections to both countries will often find themselves rowing against the tide between two very different and complex regimes. With the right specialist advice, they can navigate the cross-border challenges safely and make the best use of planning opportunities.

Understand the issues, avoid the traps, and discover ways to plan ahead in our Navigating the Atlantic series for US-connected clients.

In this instalment, we explore some of the key considerations for US citizens who are moving to the UK for the first time.

Upon becoming tax resident in the UK, individuals will become exposed to UK taxation in respect of their worldwide income and gains (subject to the remittance basis of taxation, discussed below). US persons, unlike those moving from most other jurisdictions, will also carry with them an exposure to US income tax on their worldwide income and gains. This leads to the risk of double taxation.

The double taxation agreement between the US and the UK (also known as the “income tax treaty”) is designed to provide relief from double taxation. Broadly, the treaty operates by allocating taxing rights between the two countries and, to the extent that both countries have a right to tax, providing for a system of credits that allows tax paid in one country to be credited against the liability arising in the other.

Although double taxation can generally be avoided through use of the treaty, the dual exposure can nevertheless have a significant impact on the tax-efficiency of certain types of investments – for example, where an asset is treated favourably for US purposes but is subject to higher tax rates in the UK. A classic example are US mutual funds that do not have “reporting” status in the UK1. While profits on those investments will typically be subject to capital gains rates (currently 20%) in the US, they will be subject to income tax rates (currently up to 45%) in the UK. For this reason, the UK’s remittance basis of taxation can still play an important role for US persons.

For so long as UK resident US persons maintain a non-UK domicile for UK tax purposes, they should be eligible to claim the remittance basis of taxation. By doing so, they can shelter their non-UK source income and capital gains from UK tax, provided those income and gains are not “remitted” to (i.e. brought to or used in) the UK.

Many US persons will claim the remittance basis for at least the first seven years of UK residence, when it is available free of charge. This offers a degree of administrative ease when compared to claiming treaty relief. After the seven-year point (when an annual charge becomes payable to access the remittance basis), the taxpayer will need carry out a mathematical exercise each year to determine whether payment of the annual charge is worthwhile.

In many cases, it won’t be worthwhile for US persons to pay to access the remittance basis because the global tax saving can be marginal once the residual exposure to US taxation is taken into account. However, it could be helpful for taxpayers who wish to maintain holdings in investments that are not tax-efficient in the UK (provided they can afford not to remit the income or gains arising on those assets to the UK).

US persons who choose to claim the remittance basis will need to take extra care around the timing of remittances and tax payments to ensure that tax credits are available. This is a complex accounting issue on which US remittance basis users will require specialist advice.

It is essential to plan in advance of a move to the UK, to take advantage of available tax reliefs and ensure arrangements are as efficient as possible. This is particularly pertinent for those with connections to the US due to their global exposure to US income tax, regardless of where they live. It is therefore important that advice is taken from advisors with an understanding of how the two legal systems interact; ideally before any action is taken. Please contact a member of our specialist US/UK team to find out more.

The members of our US/UK team are admitted to practise in England and Wales and cannot advise on foreign law. Comments made in this article relating to US tax and legal matters reflect the authors’ understanding of the US position, based on experience of advising on US-connected matters. The circumstances of each case vary, and this article should not be relied upon in place of specific legal advice.

1To be a reporting fund, a fund must register with HMRC as such. In doing so, the managers of the fund must agree to comply with onerous reporting obligations regarding the performance of the fund and the distributions that are made to investors. Most non-UK mutual funds will be non-reporting funds unless they have been designed with UK resident investors in mind.

In her first budget held on 30 October, the new Chancellor, Rachel Reeves, confirmed that the government will press ahead with the abolition of the non-dom tax regime.

Explore our hub for everything you need to know about relocating to the UK and discover how our Private Wealth team can advise you on making the move as seamless as possible.

Moving to the UK is an exciting life event whether it be a short-term move for work to explore business prospects or a more permanent relocation with the whole family; the UK offers an eclectic range of options to live, work and learn, from the cityscapes of London to vineyards in the English countryside and historic university towns in-between. Setting up life in a new country can feel daunting too and it can be difficult to know where to start.

Wherever you are on your journey to the UK the Private Wealth team at Forsters are here to guide you through the process and to advise you on how to make the move as seamless as possible. From Singapore to Brazil, the US to the Middle East – we also have in-depth experience of integrating UK issues into a global cross-border wealth plan.

Our Moving to the UK hub provides you with an introductory resource to understand the need to know issues, including the *UK’s approach to income tax, visas and buying property, along with key terminology and FAQs.

US citizens 1 who are UK resident beneficiaries of US trusts may be taxed twice on the trust’s income or capital gains because of the overlapping scope of UK and US taxation. The UK/USA Double Taxation Convention (the Treaty) may not serve as the desired panacea where there is a mismatch in both the timing of tax liabilities and the taxpayer’s identity under the domestic laws of each jurisdiction. This potential liability to double taxation may be an unfair cost of using such trusts to benefit members of transatlantic families. However, as outlined below, there are options for mitigating this exposure so that a UK resident may benefit from a US trust without suffering cross-border double taxation.

As noted above, a mismatch in the timing of tax payments and the identity of the taxpayer may affect the ability of the taxpayer(s) to claim treaty relief and can result in double taxation. Set out in the table below are the persons chargeable to tax in each jurisdiction on income and gains arising in US domestic trusts that are not UK resident.

| Type of US domestic trust | Taxpayer for US purposes | Taxpayer for UK purposes |

| Grantor trust | Grantors are taxable on the trust’s income and gains as if they owned the trust’s assets | Beneficiaries2 are only subject to UK tax on the receipt of payments or benefits from the trust |

| Non-grantor trust (NGT) | The trustees are taxable on the trust’s income and gains as they arise, unless “distributable net income” (DNI) is distributed to a beneficiary (where the liability rests with the beneficiary) | As with grantor trusts, a UK tax liability only arises on receipt of payments or benefits from the trust |

In the case of grantor trusts, to the extent that both a grantor (in the US) and a beneficiary (in the UK) are taxable on the same income or gain, the “exchange of notes” to the Treaty regards the beneficiary’s tax liability as being the grantor’s liability. In this way, the Treaty mitigates the mismatch in the taxpayer’s identity, albeit that when determining the grantor’s US tax liability consideration may need to be given to the sourcing of income and gains and the timing of distributions.

In the case of a US citizen who is UK tax resident for UK domestic and Treaty purposes, primary taxing rights rest with the US only in the following instances:

In general, there is no time limit for claiming a credit for any US tax liability against the UK tax where the US has primary taxing rights. By contrast, if those rights rest with the UK, time limits apply in the US to claiming credit for the UK tax against the US tax liability. If the “paid” basis of claiming foreign tax credits applies, the UK tax must be paid either during the calendar year in which the income or gain arises or, with additional planning, by the end of the following year in order to claim a foreign tax credit against the US tax liability on that income or gain.

A UK resident US citizen could be taxed twice if:

Outlined below are some options for managing such exposure.

Loans to beneficiaries could be made on interest-free and ‘repayable on demand’ terms. The beneficiary would be treated as receiving a taxable benefit to the extent that the interest paid (if any) was less than interest at HMRC’s official rate (2.25 per cent from 6 April 2020).3 For an additional-rate taxpayer, the maximum effective rate of income tax on the benefit of not having to pay interest on the outstanding loan is currently 1.0125 per cent of the value of the loan per annum.

If the net income of the trust were distributed regularly, say each quarter, to the beneficiary who is UK resident and a US citizen, any UK income tax paid on the income could be claimed as a foreign tax credit in the US, provided the UK tax was paid either in the calendar year in which the income arose or by the end of the subsequent year.4

Managing a UK resident beneficiary’s exposure to double taxation on a US trust’s capital gains is more challenging, largely due to the complex rules that apply to the UK taxation of income and gains arising to non-UK resident trusts. If the trustees are able to include gains within a trust’s DNI for US tax purposes, consideration could be given to making “capital payments” (distributions and other benefits that are not chargeable to UK income tax) to the beneficiary in the same year that the gains are realised by the US trust. This should align the timing of the tax liability in both jurisdictions, allowing double tax relief to be claimed. However, from a UK perspective, this option is effective only if the US trust has no “relevant income” (which includes “offshore income gains” arising on the disposal of non-UK collective investments without UK reporting status), because benefits are taxable by reference to trust’s relevant income in priority to its realised gains.

However, making annual distributions of the trust’s gains reduces its effectiveness as a vehicle for a family’s succession plan by removing funds from a trust that may fall outside the scope of UK inheritance tax and may be exempt from generation-skipping transfer tax for US purposes.

The beneficiary’s potential liability to double taxation may be managed in the following ways:

Whichever method is adopted, the timing of tax payments in both jurisdictions and the selection of appropriate investments (for example, US mutual funds without UK reporting status are not suitable) must also be carefully monitored.

George Mitchell is a Senior Associate in the Private Client team. He is a UK qualified lawyer and, although he does not advise on US law, the comments in this article on the US tax position are based on years of experience of advising on matters with a US connection.

1.For simplicity this article refers to the position for US citizens, but Green Card holders would generally be in the same position.↩

2.A UK resident settlor is also only taxed on receipt of a benefit provided that the trust is a “protected settlement” (which is beyond the scope of this article).↩

3.This assumes that the characterisation of the payment as a loan is respected by HMRC. This treatment could be challenged, for example, if the beneficiary had no intention to repay the loan and in that scenario the borrowed sum could also be exposed to UK tax.↩

4.In theory difficulties may arise if a person is treated as being taxed on income from a different source in each jurisdiction; a life tenant may be regarded as being entitled to the trust’s net income as of right, or as only having a right to hold the trustees to account for the net income. In practice, where the US has primary taxing rights, HMRC will give a tax credit to a beneficiary even where there is a mismatch in the source of income. ↩